Hacking Django - From a Pentester's View

We dive into Django and discuss common vulnerabilities we find during pentests.

Security issues in Django don’t usually come from exotic hacks, they come from small, easy-to-miss details. In this post, we’ll walk through common Django security pitfalls we keep running into during real-world pentests, from misconfigurations and risky defaults to recent vulnerabilities and hardening tips. If you deploy Django in production, this is a practical guide to the things you should double-check before an attacker does.

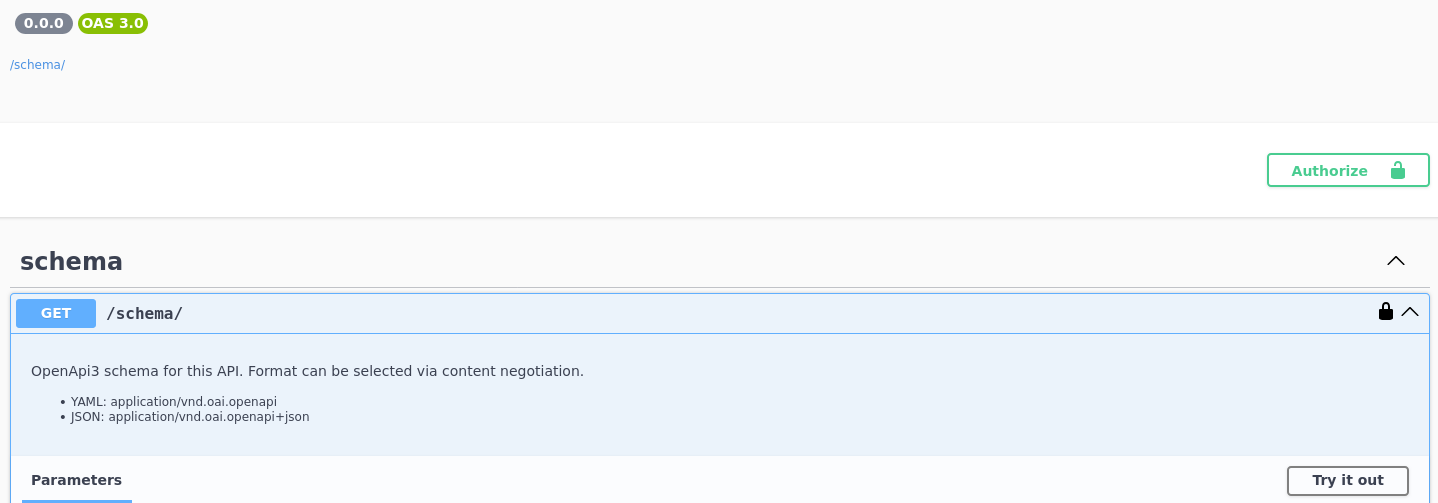

Open Swagger Access in Production

Leaving Swagger (or OpenAPI) exposed in production is another easy win for attackers. An open Swagger page often lists every endpoint, parameter, and request format your API supports, which saves attackers a lot of guessing. Even if the endpoints are protected, the documentation alone can reveal sensitive functionality, admin routes, or unfinished features. Swagger is great for development and internal use, but in production it should be locked down, authenticated, or disabled entirely unless there’s a very good reason to keep it public.

Preventing MIME Type Sniffing

Django has your back when it comes to MIME type sniffing. With the SECURE_CONTENT_TYPE_NOSNIFF setting, you tell browsers to trust the Content-Type you send and not try to guess what a file “really” is. This helps block a whole class of XSS and content injection issues, especially when users can upload or control files.

In Django 1.8 and up, you can turn this on explicitly, and starting with Django 3.0 it’s already enabled by default. If you prefer handling headers at the web server level, you can do the same thing in Nginx with the X-Content-Type-Options: nosniff header. However you set it, making sure this header is always present is an easy win for security.

Example configurations:

Django settings:

SECURE_CONTENT_TYPE_NOSNIFF = TrueNginx configuration:

add_header X-Content-Type-Options "nosniff";https://infosecwriteups.com/django-unauthenticated-0-click-rce-and-sql-injection-using-default-configuration-059964f3f898

The Django vulnerabilities that should keep you up at night

Some enterprises have been breached because they overlooked the following vulnerabilities.

“I am using ORM, I am secure.” So you think.

CVE-2025–57833 - (09/03/2025)

If your Django app talks to a database and you’re using FilteredRelation, this is something you should know about. Older Django versions had a SQL injection issue in column aliases (anything before 4.2.24, 5.1.12, and 5.2.6). If you’re fully up to date, you’re fine and don’t need to worry. Still, it’s a good reminder that even solid frameworks and “safe” abstractions aren’t magic, small things can slip through, and ignoring them is how minor issues turn into late-night problems for the whole team.

Published at: https://infosecwriteups.com/django-unauthenticated-0-click-rce-and-sql-injection-using-default-configuration-059964f3f898

Log Injection via request.path

CVE-2025-48432 - (06/04/2025)

This vulnerability allowed log injection through an unescaped request.path. An attacker could include newline characters or ANSI escape codes in the URL, which would then be written directly to application logs. This can be used to hide malicious activity, forge log entries, or poison downstream log processing and alerting systems. The issue was fixed on June 4, 2025, in Django versions 4.2.22, 5.1.10, and 5.2.2.

import logging

logger = logging.getLogger(__name__)

def my_view(request):

logger.info("User accessed path: %s", request.path)Attack:

/login\nERROR: admin logged inThis would inject fake entries into your logs.

SQL Injection via JSONField + values()

CVE-2024-42005 - (08/07/2024)

A critical SQL injection vulnerability (CVSS 9.8) affecting Django’s QuerySet.values() and values_list() when used with JSONField. By crafting malicious JSON keys, an attacker could break out of SQL quoting and execute arbitrary SQL queries against the database. This flaw enabled full database compromise in affected setups and was patched in Django 4.2.15 and 5.0.8.

# models.py

class Event(models.Model):

data = models.JSONField()

# views.py

Event.objects.values("data__user_input")If user_input is attacker-controlled, crafted JSON keys could break SQL quoting and lead to arbitrary SQL execution.

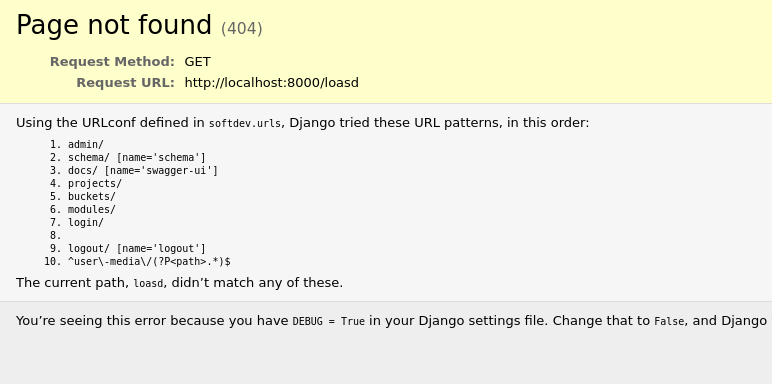

I mistakenly forgot debug flag on

If you’ve deployed a Django app, turn off debug mode and don’t reuse secrets, it’s really that simple. Stuff goes wrong in real projects: a route gets left unprotected, an API endpoint has a bug, or half-finished code sneaks into production because “no one will ever hit that URL.” When debug mode is on, Django can happily show all your endpoints. That means internal, unfinished, or poorly protected routes are suddenly visible. Instead of guessing URLs, an attacker gets a full map of your app handed to them, which makes breaking things way easier than it ever should be.

Remediation: Always set DEBUG = False in production.

Breaking the app during debug mode

Breaking Django into showing verbose errors is often way easier than people think. If debug mode is on, an attacker doesn’t need a clever exploit, they just need to make the app crash. That can be as simple as calling an endpoint with the wrong HTTP method, sending a string where the code expects a number, omitting a required parameter, or hitting a URL that triggers an unhandled exception. Even things like malformed JSON, unexpected headers, or edge-case inputs can do it. Once the error is triggered, Django helpfully renders a full debug page with stack traces, settings, environment details, and more, all right there in the response. In other words, if errors happen during normal development, attackers can usually force them too.

Debug and Secrets

Along the same lines, running Django in debug mode can quietly open new doors for attackers. When an error happens, Django’s debug pages render a lot of internal details straight into the HTML response, including environment variables and configuration values. Triggering an error isn’t hard either, it happens more often than people expect, sometimes with nothing more than an unexpected input or a malformed request.

Django does try to protect you here by masking sensitive settings with asterisks on debug pages; behind the scenes, it relies on a curated list of setting names and heuristics to decide what should be hidden before rendering the error output. The problem is that this protection isn’t foolproof.

Secrets (ie AWS tokens) can still leak through edge cases, custom settings, third-party integrations, or values that don’t match Django’s masking rules. In practice, we’ve seen this happen frequently during pentests, which is why leaving debug enabled in production is one of those “it’ll probably be fine” decisions that tends to age very badly.

When Errors Talk Too Much

Once that verbose error page shows up, the stack trace becomes a goldmine for an attacker. A Django stack trace doesn’t just say “something broke”, it shows exactly where it broke, including file paths, function names, imported modules, and sometimes even parts of the code itself. For example, a stack trace might reveal that an endpoint calls utils/payment.py or services/internal_api.py, instantly leaking internal structure and naming. It can also expose which database backend you’re using, what third-party libraries are installed, and how requests flow through the app. Here’s a simplified example of what an attacker might see:

File "/app/views/orders.py", line 42, in get_order

order_id = int(request.GET["id"])

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: 'abc'

From this alone, an attacker learns the exact file location, the vulnerable parameter (id), the expected type, and the code path that handles it. Stack traces turn guessing into certainty, making it much easier to map the application, find weak spots, and chain bugs together, all from a single forced error.

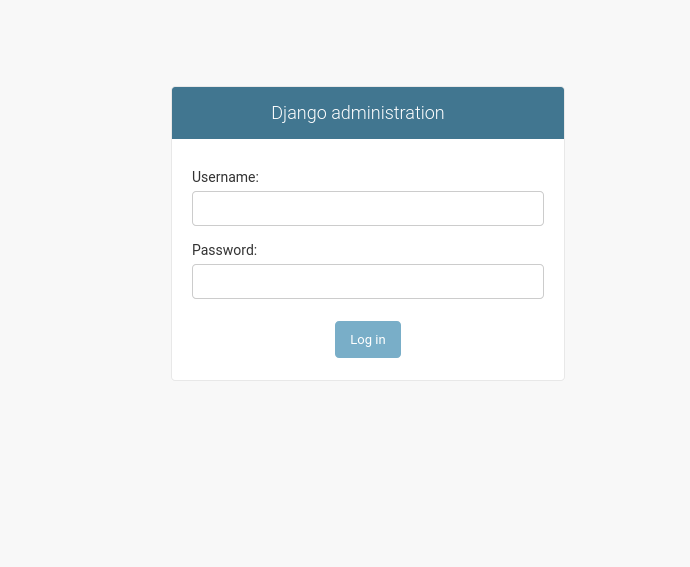

Admin Location? Sweet

If you’re using Django’s default admin URL, it’s a good idea to change it. As soon as attackers figure out you’re running Django, /admin is usually the first place they check, and it’s also a dead giveaway that your app is built with Django. Moving the admin panel to a non-obvious path doesn’t replace real security, but it does remove an easy target and reduces automated attacks. On top of that, it’s good practice to restrict access to the admin entirely for unauthorized users. If you’re using a WAF, lock it down there, and if your team works from an office with a static public IP, whitelist only that IP. Limiting who can even reach the admin page makes a huge difference and adds a strong extra layer of protection.

Raw SQL? Think again, Same for Mongo!

SQL injection lets attackers run their own SQL against your database, which means they can read, change, or delete data they were never supposed to touch. In most Django apps, this risk is low because you’re usually talking to the database through models and querysets, and Django handles escaping for you. The danger starts when you drop down to raw queries or custom SQL. At that point, Django can’t protect you anymore, so you need to slow down, think carefully about user input, and make sure you’re preventing SQL injection yourself.

Do what you do best! Develop. Let us take the lead!

Even though you may have learnt a lot during this post, there are a lot subtle vulnerabilities which may not be or may not be, related to Django framework, but weakens the security posture of your application. Let the experts do what they can do best, and find all the vulnerabilities of your application before the attackers do.

Contact me now to discuss your security needs!

Trust Boundaries and RemoteUserMiddleware

If your Django setup uses RemoteUserMiddleware together with RemoteUserBackend, you need to be very careful about where those requests are coming from. This setup trusts an incoming HTTP header (usually Remote-User) to decide who the user is, which is fine when it’s sitting behind a properly configured reverse proxy or authentication system. The problem starts when that header can be set by an external client.

In that case, an attacker can simply send something like Remote-User: admin and Django will happily treat them as that user, giving them access to endpoints ie /whoami and potentially every other API as an admin. This kind of issue shows up more often than people expect and usually comes down to missing proxy restrictions or misconfigured trust boundaries.

Multi-Login Methods

By default, a typical Django setup can end up supporting more than one way to authenticate users, including session-based login and authentication via HTTP headers.

While session authentication is generally safe when used correctly, allowing header-based authentication as a secondary method can introduce unnecessary risk. HTTP Basic Authentication simply sends a Base64-encoded username and password with every request, which is not encryption and offers no real protection if misused or exposed.

If this method is enabled unintentionally or without strict controls, it increases the attack surface, makes credential leakage more likely, and can bypass assumptions developers make about how users are authenticated. In many cases, it’s safer to disable header-based authentication unless it’s explicitly required and carefully locked down.

Writing to cache

Think of Django’s cache as a convenience feature that can turn dangerous if it’s not locked down. By default, Django stores cached values using Python pickles. That’s fine as long as Django is the only one writing to the cache, but if an attacker can write to it, things get ugly fast. Pickles can execute code when they’re loaded, so cache access can turn into remote code execution (RCE).

Django caches can live in Redis, memory, files, or a database. Redis and database-backed caches are the most common trouble spots (think Redis injection or SQL injection), but file-based caches can be just as bad. If the cache directory is writable by an attacker, they can drop a malicious pickle file and wait for Django to read it. When that happens, their code runs. Maintainers consider this “expected behavior,” so it’s on you to secure the cache location and access.

Here’s a simple example of how file-based cache abuse can look:

import pickle, os

class RCE:

def __reduce__(self):

return (os.system, ("id >/tmp/pwned",))

open('/var/tmp/django_cache/cache:malicious', 'wb').write(

pickle.dumps(RCE(), protocol=4)

)Bottom line: never treat the cache as a safe place for untrusted data. If someone can write to it, they might be able to run code on your server.

More here: https://hackerone.com/reports/1415436

Now What?

The findings we encountered could have led to meaningful impact if abused, which reinforces why frequent, well-scoped security testing is so important.

Contact us now at info@cybervelia.com and let us uncover your Django vulnerabilities, before attackers do.